Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Archie Connelly III was born May 12, 1950, in Chicago, and was raised by his parents with his siblings on a farm in Zion, Illinois.

Connelly earned a bachelor of arts degree from Southern Illinois University in ceramics in 1973. While at SIU, a show of Connelly's work at The Gallery at The Wesley Foundation Building warranted a healthy write-up in the student newspaper, The Daily Egyptian, complete with a portrait of a grinning Connelly displaying some of his ceramic creations. The image of the argyled, bearded Archie to the right likely came from the same photoshoot.

After graduation, Connelly moved to San Francisco, where he worked in theatre design for groups like the Angels of Light, the Cockettes, and Warped Floors and—according to a biography from one of his early shows—started a band called The Decorators.

In 1980, Connelly moved to New York City, specifically to the East Village, then the heart of a burgeoning art scene which blended elements of camp, craft, grafitti, and punk into an explicitly gay art movement. Connelly quickly became a mainstay at both the galleries and parties that flourished in the East Village. He held his first group exhibition in 1980 at Artists Space in TriBeCa and his first solo show the following year at the influential FUN Gallery.

Connelly's early New York shows were dominated by home furnishings layered with aggregations of faux pearls, glass gems, pieces of costume jewelry, sparkly aquarium gravel, and even the occasional crushed and painted eggshell.

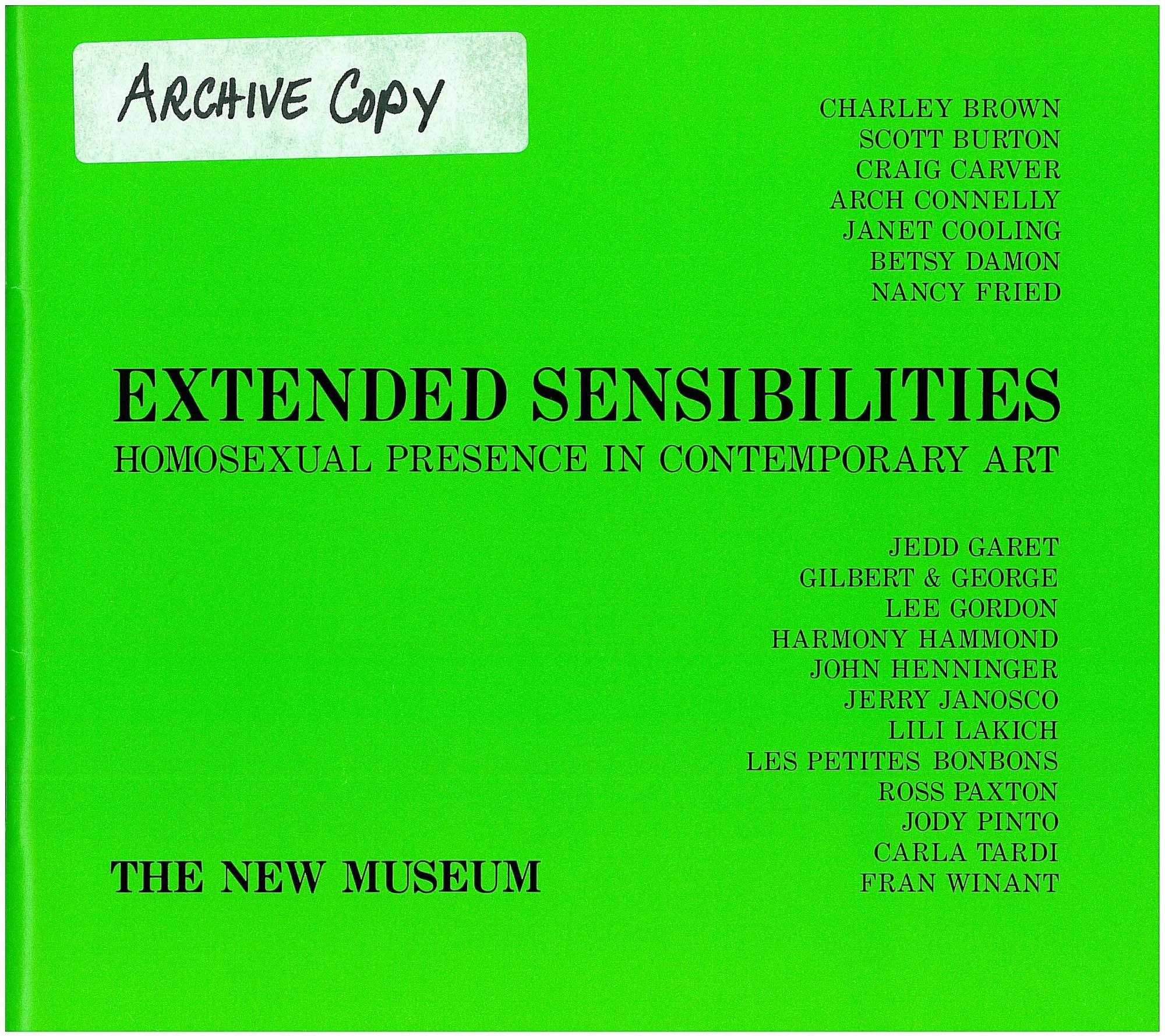

In 1982, Connelly participated in the exhibition "Extended Sensibilities" at New York's New Museum. The show was billed and recognized as one of the first museum shows in the United States to feature art solely by artists who identified as homosexual and inclusion very publicly outed the individual artists at a time when conservative politics were on the rise. Curator Dan Cameron credits a discussion with Connelly about "the connection between gay sensibility and mannerist art" as inspiring the show.

He expanded into coating other objects (such as the model airplane at right) with his trademark faux-lapidary and blending the jewel-work with paintings on surfaces as varied as plywood and moire silk in the mid-1980s.

Next came thick coatings of sequins and glitter over bold colors or subtle gradations of color. At about the same time, Connelly produced his most noteworthy collages: assemblages which combined clippings from seed catalogs, jewelry brochures, and porn magazines with his intricate beadwork.

Even as he added techniques, Connelly continued to refine his earlier approaches, leading not to distinctive "periods" in his work, but emergences and branchings instead. This is demonstrated by the last works he created: sequin-encrusted panels marked by incised curves which seemed at least somewhat inspired by the grafitti artists involved in the East Village scene.

Like many of those involved in that scene, Connelly died of AIDS, as did his partner, Ahbe Sulit. Connelly was 43.

In the decades following his death, Connelly has received growing recognition for his part in an art movement which continues to reverberate throughout American culture and around the world.

Arch Connelly (back row, second from right) as a first-year SIU student with his Allen Hall cohort. (Right click and open in a new tab to enlarge)

From Southern Illinois University. Obelisk, vol. 55, 1969, p. 382. Available through the Internet Archive.

Archie Connelly at SIU ca. 1972.

Photograph by Dennis Makes of the Daily Egyptian, courtesy of Special Collections Research Center, Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Arch Connelly ca.1985.

Photograph courtesy of artnet.com.

Memories of Archie

Memories of Archie

Extended Sensibilities: Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art

by

Extended Sensibilities: Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art

by

Cornips, Marie Hélène. Minder kan het niet: exuberantie nu = Less is a bore: exuberance now. Groninger Museum, 1989.

Cornips, Marie Hélène. Minder kan het niet: exuberantie nu = Less is a bore: exuberance now. Groninger Museum, 1989.

Arch Connelly: Works 1981 - 1993

Arch Connelly: Works 1981 - 1993

Love Among the Ruins: 56 Bleecker Gallery and Late 80s New York

Love Among the Ruins: 56 Bleecker Gallery and Late 80s New York

In one picture shown here, Culture and Landscape, 1985, a purplish expanse of mountains and mesas in acrylic on silk is half obscured by a wide, irregular belt of multicolored faux pearls. The work is round, a tondo — a typical format for Connelly, who certainly used the usual rectangles but, being in no way himself square or straight, just as often escaped them — and is encircled by a showy gold chain as a frame. Since the "landscape" named in the title must be the mountains, "culture" must be the band of pearls that spreads to overtake them, a smart, witty conceit that is probably in part a pun on cultured pearls but is also a larger statement: Cheap, devalued, trashy, artificial, the pearls nevertheless, or therefore, imply a culture that is eye-catching, glamorous, and transformative — the kind of culture that Connelly worked to realize by living his life.

— Frankel, David. “Arch Connelly, La MaMa La Galleria.” Artforum, vol. 50, no. 9, 2012, p. 308.

Domergue, Denise (editor). Artists Design Furniture, Harry N. Abrams, 1984, p. 64.

Domergue, Denise (editor). Artists Design Furniture, Harry N. Abrams, 1984, p. 64.

I consider myself a sculptor. Even when I paint I think of my work in terms of objects. I wanted to make sculpture that had a utilitarian function as well as a purely aesthetic one because I always felt it was silly to make sculpture that didn't do anything.

Furniture should function on as many levels as possible. Whether these pieces are seen as sculpture or merely as tables is fine, but it makes it better if people can integrate the two and get involved in the ambiguity of form, function, and aesthetic possibilities.

I've been through the sixties, seventies, high tech, and so on. I like geometry, but I reject the coldness of Minimalism. The whimsy of rococo, Futurism, and artists like Calder and Westermann have influenced me a great deal. I love the heavy emotion and overdone darkness of nineteenth-century art. I consider myself a Mannerist since I use so many ideas borrowed from the past. Though I love theatricality and utilize kitsch, my criteria is not based on making fun of things. I believe in the decorative and that things must be beautiful. I'm a stickler for craftsmanship and to me what I do is well crafted.

I amass elements and they stay around the studio for months until I understand how best to utilize them and what kinds of associations I want. The idea of things being underwater appeals to me; an aquarium is a picture of little diorama, and like museum-type space that you look into, so I use aquarium supplies. They are mass produced and all the same predefined shapes that I can use repeatedly in different permutations as basic forms. I like the fact that people can bring their associations to them, although my recent work uses more abstract materials so the reaction be be on a more aesthetic level.

— Connelly, Arch. “Arch Connelly.” Artists Design Furniture, edited by Denise Domergue, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, NY, 1984, p. 64.

Arch Connelly: More About the Artist by Cassie Wagner is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This license grants you permission to copy this guide, in part or in its entirety, as long as you follow license terms and attribute the author. There’s no need to ask for permission.